The Elusive Nature of Reality: Why We Can Never Know What is Truly "Real"

- tanisha

- Dec 7, 2024

- 5 min read

What if everything we experience — the sights, sounds, and sensations — is only a creation of one’s mind, shaped by our perceptions and senses? The idea that the world we perceive may not be the world that truly exists challenges our understanding of reality itself. How do we, as a human race, know what is inherently real? The paradox presented has baffled all types of thinkers, scientists, and philosophers, but has a singular consensus: we can never know what is truly real. After all, our reality is subjective, shaped by the limits of our senses, consciousness, and perceptions. It is truly unknowable.

So, is the universe "real?" Let's start with the basics:

Our interpretation of reality is ambiguous and limited. René Descartes, a famous philosopher, argued that all knowledge must be questioned, even the most seemingly obvious. In his work Meditations on First Philosophy (1641), Descartes states, “I think, therefore I am,” meaning that doubting one’s existence is proof of it. Essentially, his statement argues that even if we doubt everything, our very ability to doubt confirms our existence. He also questioned the reliability of the senses, saying that they could be manipulated by an "evil demon” which creates a false perception of reality. His skepticism implies that we cannot trust our senses to reveal an objective truth because of potential deception. An example of this is derealization – a psychological phenomenon that distorts reality for an individual, making the world feel unreal. I have personally experienced derealization, where familiar surroundings felt illusory. My feelings of complete disconnect caused me to question everything, especially the idea of an objective state of being. This demonstrates how malleable and easily altered our cognition can be, directly supporting Descartes's claim that our senses are unreliable and that what we perceive as real in the moment can be fabricated by the mind. Another example is when dreams seem real as they are happening - is that the product of a manipulation of our senses or the emergence of an alternate reality? Ultimately, our cognitive interpretation of the world can be easily distorted and manipulated.

Descartes’s claims about questioning the nature of existence because of our deceptive senses are supported by modern neuroscience, which shows how fluid our perception can be, as it is a fabrication of the mind. Studies reveal that our brain shapes our awareness of reality. For example, neuroscientist David Eagleman, with his work Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain (2011), explains that our perception is a mental construct and our “reality” is a subjective experience based on the limitations of our senses and brain, thus making it uncertain. The brain constantly predicts what will happen next, leading neuroscientists to argue that our experience is a “controlled hallucination”: a mental construct based on thoughts. This means what we interpret as "reality" is not a direct reflection of the world around us, but what our brain creates based on predictions and sensory input. Since this understanding is subjective, we can never know if we perceive the world as it truly is. This notion aligns with Descartes’s skepticism, suggesting that our view of reality is not an objective truth, but rather a subjective creation of the mind.

Then, how can we use our senses to reveal an external world when our subjective experiences make reality uncertain? The philosophy of solipsism takes these doubts further, stating that the only thing we can be sure of is one’s mind and everything else experienced is a projection of our consciousness. Irish philosopher George Berkeley’s idealism heightens this idea and argues that the existence of objects entirely depends on what is perceived. His famous proclamation, “esse est percipi” (“to be is to be perceived”), essentially states the external world is an illusion only in the mind of the viewer. But does this make our mind the only “real” thing? Since we cannot directly access the brains of others, how do we know that other minds exist the same way as our own? We cannot even understand how everyone’s perceptions differ. Therefore, the limits of human cognition and each individual’s subjective experience imply that the nature of reality itself is always uncertain.

In addition to these philosophical doubts, theories of quantum mechanics reveal that reality may be even more fluid than imagined. The observer effect in quantum mechanics states that observing a system can alter its state. It is proved by the double slit experiment where particles are shot through two slits in a barrier. Scientists found that when we see the particles, they behave as particles, but when we're not watching, they exist in a state of probability and are spread out like waves. So, does reality depend on observation? This experiment indicates that reality is not fixed (until measured), implying that observations and our interactions must influence the outcome. It also questions whether an observer-independent reality exists. What happens when we are not looking? According to quantum mechanics, we might not even know the true nature of existence when we’re not observing it. Hence, it is impossible to fully understand what's "really real" because our perception and measurement of reality always shape it. As a result, observation seems to affect what we see, hinting that reality might be unknown until we interact with it.

Whether it’s Descartes questioning our senses, neuroscience showing how our brain constructs our experience of the world, solipsism arguing that only our mind can be known to exist, or quantum mechanics suggesting that observation shapes existence; each of these theories connects to a fundamental truth: we can never fully access or understand the nature of reality. Furthermore, most of the mysteries of the universe focus on the existence of celestial objects and outside life, theories about the origin/end, the multiverse, alternate realities, and much more. All of this revolves around the idea of reality. Our life in this world contains limitations of our perception, cognition, and the tools we use to measure it. So, what does this mean for how we live in the world? Despite the uncertainty, we continue to interact with the world and beyond. What is “real” is not fixed, so our subjective experience is all we have and what we will ever know. Our perception, cognition, and scientific understanding are inherently limited and different, preventing us from ever understanding what is truly real. Our reality is what we make of it, yet its nature remains mysterious.

Reality Beyond Our Knowledge: The Universe

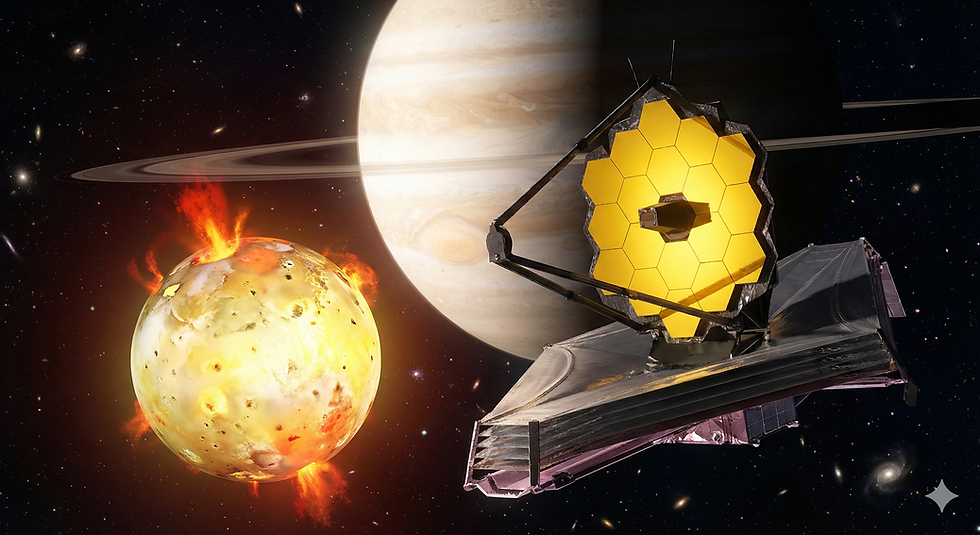

Out understanding of the unknown is proof we can never truly know the universe in its entirety either. Our senses and cognition shape how we experience the cosmos, and even the tools we use to observe space—like telescopes or particle accelerators—are still extensions of our perception, limited by our human abilities.

For example, when we look at distant galaxies, we're not directly experiencing them; we're interpreting data gathered by instruments. The same is true for time and space: Einstein’s theory of relativity shows that time isn't the same everywhere and changes depending on the observer's position, meaning our experience of time in the universe is subjective.

Quantum mechanics further complicates this. The observer effect suggests that the state of reality can change depending on whether or not we are observing it. This raises the question: Does the universe exist in a certain way when we’re not looking at it, or does it only "become real" when we observe it?

All of this suggests that, while we can make models and theories about the universe, we can never fully know it as it is, just as we can never fully know the true nature of our own reality. The universe, like our personal experiences, is shaped by our perception and understanding, and that understanding will always be limited. Our mission to understand the cosmos is really a quest to understand the limits of our own minds.

Comments